Old vaccine, new tricks? Unlocking the BCG vaccine’s potential

Could a century-old vaccine offer clues for designing the vaccines of tomorrow? Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, wants to find out.

One of the world’s oldest and most widely used vaccines, the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) tuberculosis vaccine may at first seem like an unlikely source of inspiration. Yet previous research suggests its effects may extend well beyond preventing TB. For reasons that remain unclear, the BCG vaccine also protects newborns and young infants against other bacterial infections and some viral infections. There’s even some evidence it can reduce the severity of COVID-19.

Its benefits may lie in its origins: “Unlike many newer vaccines, BCG is made from a live, weakened germ, and may offer unique mechanisms of protection,” says Levy. “It’s critical that we learn from BCG so we can better protect newborns, whose immune systems are distinct from those of adults.”

Small babies, big data

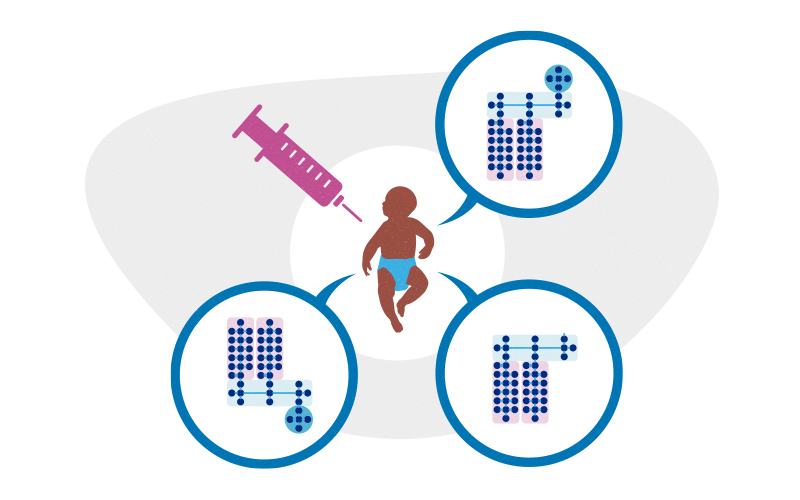

To better understand BCG’s potential, Levy’s group partnered with the Expanded Program on Immunization Consortium (EPIC), an international team studying immunization in early life. Led by Joann Diray-Arce, PhD, in Boston Children’s Precision Vaccines Program, the researchers compared small samples of blood from newborns in the West African country of Guinea Bissau, taken before and after vaccination. With the help of co-investigator Hanno Steen, PhD, they used cutting-edge techniques called metabolomics and lipidomics to analyze the samples.

Crunching all the data, they found that infants who received BCG at birth had profiles of metabolites and lipids in their blood that differed from those who hadn’t yet been vaccinated. These were in line with changes in the production of cytokines, key chemical signals that rally the immune system.

The findings were similar in two other groups of infants who received the BCG vaccine through a Human Immunology Project Consortium study. Notably, the changes in blood metabolites, lipids, and cytokines were similar with all three BCG formulations used in the different studies, suggesting common pathways of protection.

“We now have some biomarkers of vaccine protection that we can test and manipulate in mouse models,” says Diray-Arce.

That’s the next step, and Levy is excited to see where it will lead.

“Old vaccines like BCG seem to activate the immune system in a very different way in early life, providing broad protection against a range of bacterial and viral infections,” Levy says. “There’s much work ahead to better understand its protective effects and use that information to build better vaccines for infants.”

The study, published in Cell Reports, was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Precision Vaccines Program, and the Mueller Health Foundation.

Learn more about the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Related Posts :

-

Emerging protein-based COVID-19 vaccines could be game-changing

Current messenger RNA vaccines appear to offer at least some protection against new SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Omicron, especially for people ...

-

As COVID-19 fuels opioid deaths, researchers look to create an anti-opioid vaccine

A project that began one year ago at Boston Children’s Hospital to develop an anti-opioid vaccine is starting to ...

-

100 years after the advent of TB vaccines, formulations vary widely

Each year, more than 100 million newborns around the world receive vaccinations against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or TB, which infects about one-quarter ...

-

Small samples, big data: A systems-biology look at a newborn's first week of life

The first week of a baby’s life is a time of rapid biological change. The newborn must adapt to ...